Commissioner Giner’s mission: remove the obstacles keeping San Diego from resolving the border sewage crisis

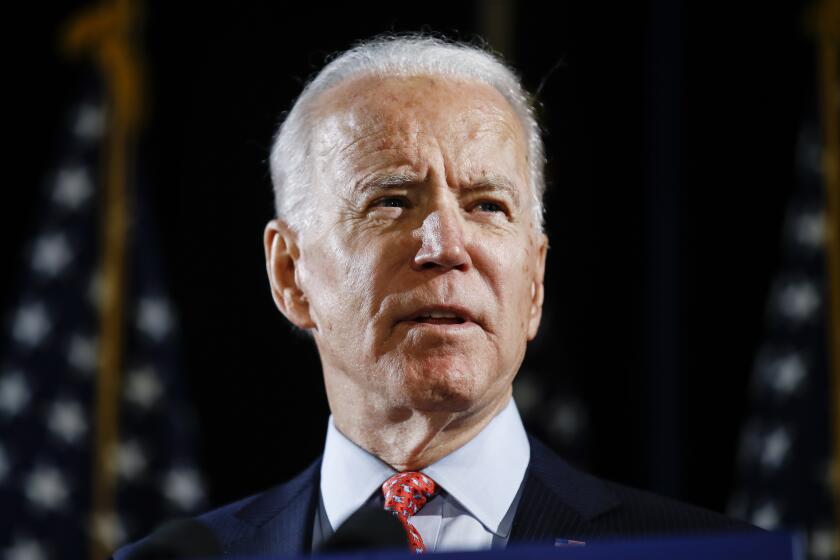

Biden appointee tasked with fixing aging infrastructure contributing to longstanding pollution at U.S.-Mexico border. ‘Priority No. 1 is safety.’

Bureaucratic blunders, mismanagement, partisan politics, cross-border politics, understaffing, equipment failures.

The list of reasons for the longstanding sewage crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border is long.

At the center is the International Boundary and Water Commission, the binational agency responsible for preventing water pollution in the Tijuana River and southern San Diego County shorelines. It has been severely handicapped in its task. The result: beach closures due to contaminated ocean water, economic losses and growing concerns about the long-term health impacts caused by breathing, smelling and touching sewage-tainted water.

Each country is represented by a commissioner appointed by their respective presidents. Commissioner Maria-Elena Giner, appointed by President Joe Biden in 2021, inherited the broken system. She’s been trying to steer the federal agency in the right direction ever since.

In San Diego, the U.S. section of the IBWC oversees the South Bay International Wastewater Treatment Plant, which has been in disrepair for the past two years. A similar plant in Baja California has been inoperable for far longer, forcing the U.S. plant to take more wastewater than it was designed to handle.

That’s taken a toll on the aging facility, which first came online in 1997. The plant’s five primary treatment tanks have been out of service for a year and, in the past, frequently clogged with sewage, garbage and sediment — discharging millions of gallons a day of partially treated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean. As a result, IBWC’s damaged facility has racked up numerous clean water violations.

Giner outlined the agency’s challenges in a recent interview.

Q: Why has the IBWC been hampered by so many funding limitations?

A: The U.S. side of the IBWC operates under the foreign policy guidance of the Department of State. That means its budget is submitted through that department and appropriated by Congress.

But as a classified “sub-component” of a department that handles foreign policy and foreign relations, the binational IBWC does not qualify for domestic investments, such as funding to replace the nation’s crumbling roads and bridges. Additionally, the State Department invests the least of its $84 billion budget into its international commissions.

That has severely limited the agency’s ability to respond to infrastructure and other needs across the border.

“How much do you think we got in the Inflation Reduction Act,” said Giner. “Zero. How much do we get in the Bipartisan Infrastructure bill? Zero. Why? Because those are domestic programs. And since our budget falls in Foreign (Operations), we never get pulled into those conversations.”

Q: Has that been a challenge for an agency that oversees international bridges, dams, wastewater treatment plants and other ongoing projects along the U.S.-Mexico border?

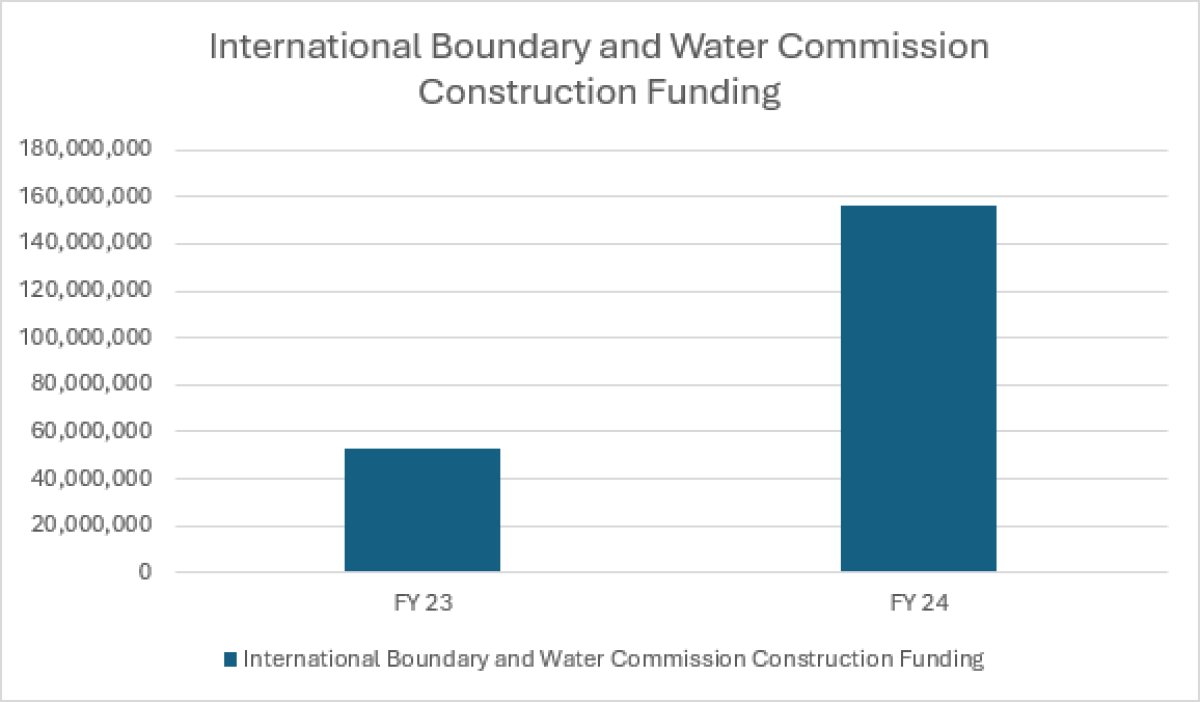

A: Giner said it has. The IBWC’s construction budget has repeatedly been smaller than some of San Diego County’s smaller cities.

From 2010 to 2020, it worked with an average of $40 million per year for salaries and $31 million for construction for all projects and obligations along the nearly 2,000-mile international border. However, the agency’s needs are significantly greater, making it challenging to address critically underfunded projects year after year.

During those 10 years, the IBWC spent only $4.1 million on maintenance and repairs to the South Bay plant. All other work that its contractor recommended was pushed back, even after the agency redirected funds from other projects to cover costs.

Repairing and expanding the South Bay treatment plant, which alone requires nearly $1 billion, is a priority, agency officials said. Simultaneously, the IBWC is trying to prevent other crucial projects from posing threats to public safety. Among them are more than $940 million in needed flood control protection in the Rio Grande and levee rehabilitation in the Tijuana River.

“I’ve had to triage it all into buckets,” said Giner. “Priority No. 1 is safety. Is it a safety issue for employees, for the public? The wastewater treatment plant in San Diego is one of them. The second one is things that are urgent that if we don’t take care of will become a safety issue. And (the third) is things that are working. It’s running on four spares, but I cannot get to you yet.”

A sigh of relief came in March. Congress approved a $103 million boost to the IBWC’s annual construction budget, which Giner said will largely be used to fix the dilapidated South Bay plant. The legislation also greenlights the IBWC to receive funding from other federal and non-federal entities, such as state and local governments and nonprofits, significantly boosting its power to finance repairs.

Because of how the agency is budgeted, Giner said “it’s really up to us, it’s up to communities, as well as members of Congress, to be put in (supplemental spending bills).”

Rep. Scott Peters and other San Diego area Congress members sponsored amendments to boost the IBWC’s budget in the Fiscal Year 2024 State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Bill. Along with local government leaders, environmental advocates and community leaders, officials continue to push the federal government for additional funding to double the South Bay plant’s capacity.

The latest request came on Friday. Peters and Texas Congressmember Veronica Escobar, along with eight of their colleagues, requested $278 million for the IBWC’s construction budget in the Fiscal Year 2025 Appropriations Bill. They also asked for $89 million for salaries and that the same language allowing the agency to receive money from other federal and non-federal entities be included in the legislation.

In a letter to members of the Committee on Appropriations and House Appropriations Subcommittee, the lawmakers said the IBWC “continues to face obstacles as it seeks to fully carry out its mission.”

“This vital investment will continue to help the IBWC keep pace with its maintenance backlog while also giving it the ability to focus on projects like levee construction and drought mitigation across the border states,” the letter read.

Q: The skeleton crew managing the South Bay plant is growing. The first of treatment plant’s five primary treatment tanks just went online late last month. And the plant is expected to comply with water quality standards by August. What’s changed?

A: Since becoming the top U.S. official at the international agency, Giner has worked to overhaul operations at the South Bay treatment plant to bring it up to speed after years of poor organization and underinvestment.

“It’s changing us from (being) a reactive maintenance agency to a proactive maintenance one,” she said. “We don’t hear the Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Reclamation say, ‘We need money for this, or we need money for that’ because they are proactively maintaining their infrastructure.”

Three things she’s ordered for the IBWC, including at the South Bay plant:

- A manpower study to identify staffing levels needed to execute projects and prevent increased workload for existing staff, especially when facing a 30 percent vacancy rate and when one out of three employees across its 12 offices are at or near retirement age;

- An asset management system that prioritizes repairs and generates work orders annually to maximize the lifespan of its infrastructure while reducing costs;

- A 20-year capital plan that will outline the timing and financing of capital projects.

“The agency, in the past, has denied not having a capital plan,” said Giner, adding that a 2020 internal audit of the South Bay plant found improper maintenance and accounting practices. “But when I came here and I saw (their plan), I said, ‘No, this is not a capital plan.’”

Giner’s predecessor was Commissioner Edward Drusina, who served from 2009 through 2018. He stepped down in May 2018 amid lawsuits from South County cities that the IBWC had failed to control the sewage crisis.

Agency officials had said his departure was a routine change in leadership ordered by the current White House administration. But South County leaders such as former Mayor Serge Dedina said then that he asked “for his resignation or firing” because “he did almost nothing to advance efforts to clean up the Tijuana River.”

Though not outstanding, according to a nonprofit that conducts the Best Places to Work in Federal Government rankings, the IBWC’s leadership has become incrementally more effective over the years since Giner joined the agency.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.